An undisciplinary journey

The title of this post refers to a wonderful paper by Haider et al (2017), which reflects on the experiences of a group of early career researchers working within sustainability science. They use the term ‘undisciplinary’ to articulate the space occupied by these scholars in the absence of any strong affinity to a traditional discipline. This resonated with me. It evokes on some level an iconoclastic, counter cultural liberation from a rigid tradition, but at the same time an uncomfortable feeling of not fitting in, of doing something wrong or forbidden, ‘this is not how we do things here’.

I studied Physics as my undergraduate degree, gearing my specialisation towards the theoretical maths heavy areas of cosmology and particle physics. Having being engaged in a summer research project during this time, I had decided that academic research was something I wouldn’t mind doing as a career. Thus, during my final year I began to apply for PhD programmes. My grades were good, but the area I had chosen to focus my efforts, cosmology, was at the same time one of the most mathematically challenging, and most competitive areas. Ultimately I was unsuccessful in this. Somewhat despondent I began to look into alternate career paths, by chance however I stumbled upon an advertisement for an EPSRC funded PhD studentship seeking a mathematician or physicist for a project relating to sustainability, an area which I had a political interest in. I applied, and was successful.

In 2015 then I joined Nottingham University’s Laboratory for Urban Complexity and Sustainability with the working project title ‘physical modelling of sustainable urbanisation’. In practice this was supplemental funding for the Leverhulme Trust funded project ‘Sustaining urban habitats: an interdisciplinary approach’ of which I was an active part, sharing office space with other students from the project.

This ambitious project drew together a broad range of researchers from across the social and natural sciences with the aim to “transform our understanding of how sustainable cities, and by extension our species, can be”. Thus it was intended that I would utilise my ‘expertise’ as a physicist, with an analytical modelling background and a personal interest in environmentalism, in this interdisciplinary environment. Of course the PhD is a singular endeavour, so this meant carving out my own research project within the context of the wider group’s shared aims. Nevertheless my immersion in an interdisciplinary environment strongly influenced the evolution of my research, particularly regarding my own personal epistemology.

Initially my research was intended to focus solely on the case of an entropic indicator for sustainability, a framework would have been developed for its measurement at the urban scale, with reference to what other components must complement it to give a more complete measure of sustainability.

As the research panned out however, it became clear that the entropy approach was severely limited in its application. The decision was thus made to abort developing this case further. The failure of this approach to bear fruit proved to be integral to the evolution of my thinking, and marked a fundamental shift in my ontological and epistemological assumptions. I became very critical of what I have perceived as natural scientists attempting to prescribe ‘rigour’ (as I had attempted to do myself) to areas typically dominated by the softer sciences, as well as social scientists borrowing little understood concepts from the natural sciences, which through their unfamiliarity to peer reviewers in the area, escaped proper scrutiny.

Coupled with this disillusionment with my previous epistemological grounding, my work surveying the conceptual history of sustainability had revealed that there existed no clear theoretical origin or rationale of the ‘three pillar paradigm’ with which I had centred my work upon. Along with Ramsey (2015)‘s argument that “We cannot define our way to clarity” (p1085), and the pluralism of voices fostered by my interdisciplinary research environment, my thinking had taken a dramatic departure from my original research design which was grounded within a positivist framework. How could I salvage a research frame that I no longer believed in? Did this mean my original research design was poor? Yet paradoxically without undertaking this work I wouldn’t have undergone such a shift in thinking.

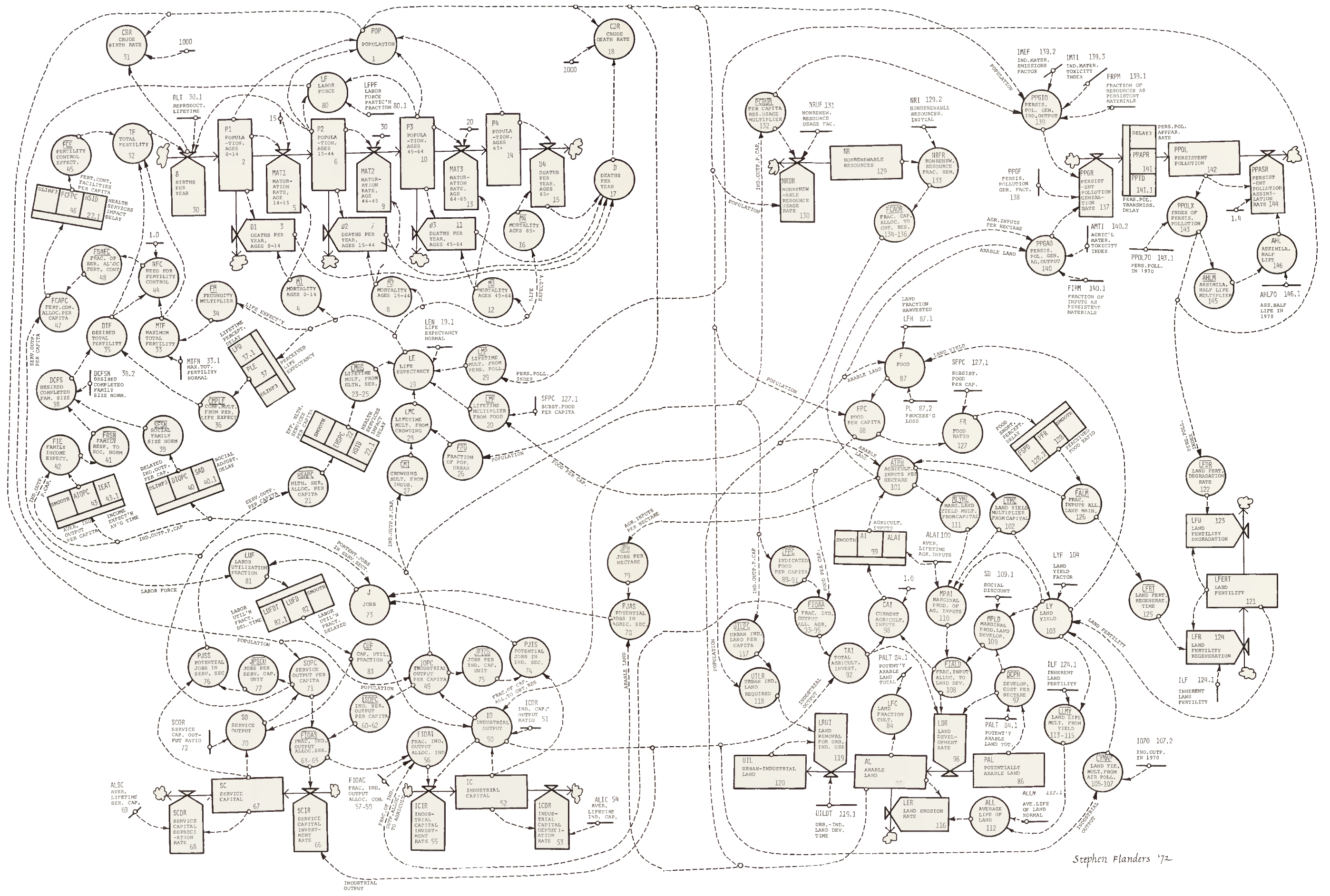

With my faith in my research shaken I turned to friends and colleagues for advice in directions I could take to salvage my PhD. It was through discussions with Brigitte Nerlich, and later her partner David Clarke, that the system dynamics work of Jay Forrester was mentioned as a potential avenue for exploration. I had come across this work in passing at various points in the literature through the oft cited Limits to Growth report by the Club of Rome. Furthemore I had been fascinated by a reproduction of the graphical presentation of the underlying World3 model in Pasqualino et al (2015), reproduced again below. I therefore went on to explore this model as a potential for developing an alternative approach for addressing my original endeavour to better understand ‘urban sustainability’.

Thus my PhD journey represented a shift in my worldview from a primarily positivist tradition featuring textbooks full of foundational ‘facts’ to a constructivist realm where even the foundations of knowledge are contested. It captures an escape from a disciplinary silo into an area which is rich in interdisciplinary, post-disciplinary, and ‘undsiciplined’ understandings.